In a previous article, we discussed the important topic of concussions (also known as mild traumatic brain injury or mTBI) and their incidence, mechanisms of injury, and signs and symptoms. We also identified that there is no objective way to diagnose mTBI/concussions. As a result, medical providers look to clinical criteria or checklists to make their diagnoses. In this review, we will update you on the ever-expanding arena of the classification of concussions and why it is significant.

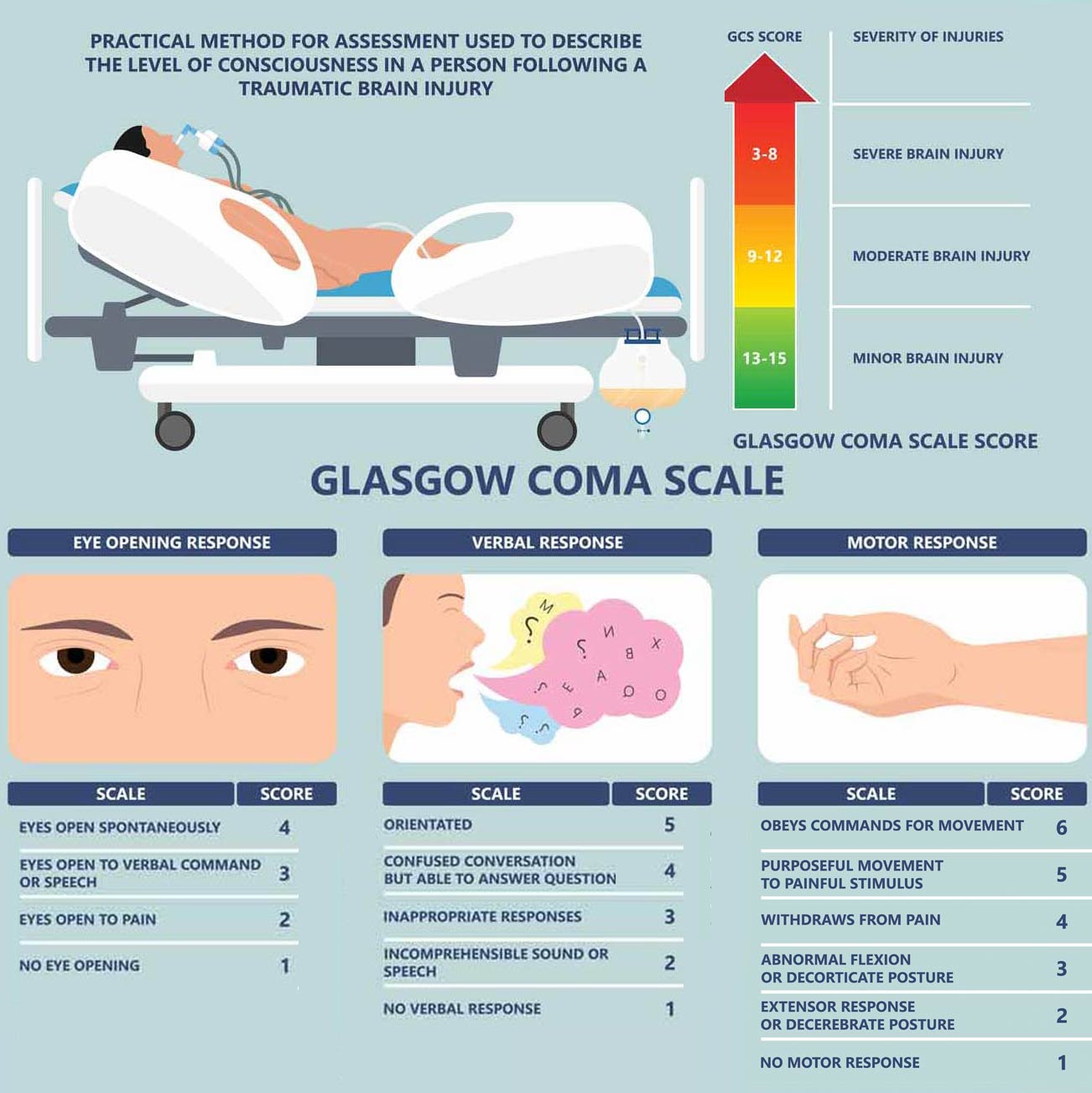

Early in our understanding of traumatic brain injuries, much emphasis was placed on how a person who sustained a head injury fit into a checklist called the Glasgow Coma Scale.

As shown in the diagram, it was based on three areas of response that a head-injured individual needed to demonstrate. It included eye-opening, verbal response, and a physical response to certain stimuli. This was then placed into a scoring table and the injury could be identified as being mild, moderate, or severe. The problem with this score, however, was that its design was geared to more severe types of brain injury and failed to detect many of the nuances with many cases of mTBI/concussions.

Later, a number of medical organizations refined the diagnosis of mTBI to evaluate four criteria: loss of consciousness, post-traumatic amnesia, mental status, and neurologic signs. The problem again was that the different medical organizations could not agree on the quantification of each criterion. For example, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (1993) and the World Health Organization (2004) stated loss of consciousness for greater than 30 minutes was required. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ definition (1999) required loss of consciousness of less than 1 minute. Some graded concussion severity as mild, moderate, and severe based on loss of consciousness.

These classifications, however, were called into question when recent research indicated that only about 10% of individuals who sustain a concussion lose consciousness. More importantly, this study found that those with mTBI who did not lose consciousness had a higher risk of future dementia. Clearly, loss of consciousness cannot be the focal point of any classification.

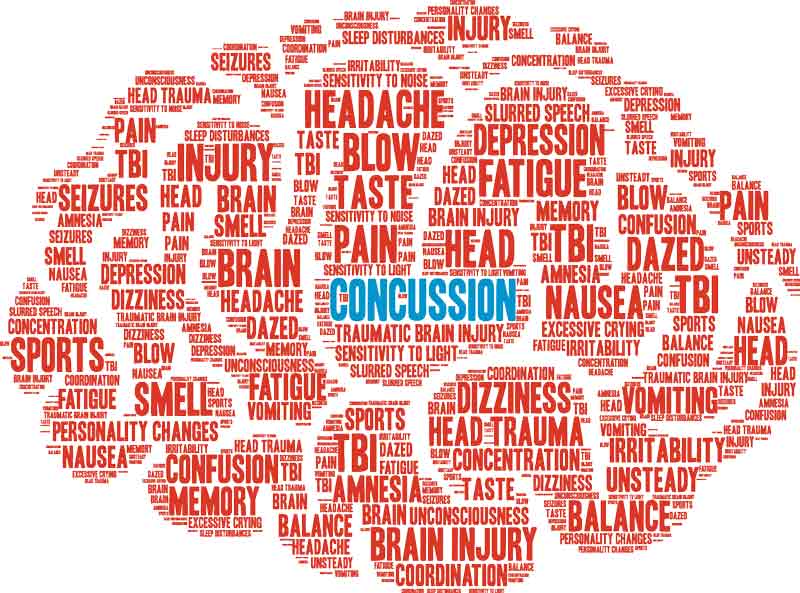

Important in the strategy of any classification is the ability to create strategies for diagnosis and later treatment. As a result, the type of impairment has become a useful tool in the classification of concussions. Each individual suffering from mTBI may display differing degrees and types of impairment depending on the extent and location of the brain injury. Below is a diagram that attempts to demonstrate the numerous types of brain functions that a traumatic brain injury can affect.

Understanding that concussions represent a variety of locations and types of brain injury, the following characterization of subtypes for concussions has been developed: cognitive/fatigue; vestibular; ocular; post-traumatic migraine; anxiety/mood and two concussion associated conditions with cervical strain and sleep.

The cognitive/fatigue type of concussion demonstrates symptoms of fatigue and difficulty concentrating. The vestibular type shows symptoms of dizziness, fogginess, and nausea. Ocular shows difficulties with vision, pressure behind the eyes, and/or difficulties with visually based activities. Post-traumatic migraine concussions have symptoms of a pulsating headache associated with nausea, photosensitivity (sensitive to light), or phonosensitivity (sensitive to sound). Cervical-type concussions have symptoms of headache, neck pain, or numbness/tingling of the extremities. Cervical-type concussions can be associated with other subtypes. Sleep disturbance refers to challenges with falling asleep, maintaining sleep, and can include feelings of being excessively sleepy or insomnia. Sleep disturbances can be associated with other subtypes. Finally, anxiety/mood type concussions demonstrate anxiety, hypervigilance, a feeling of being overwhelmed, sadness, and/or hopelessness.

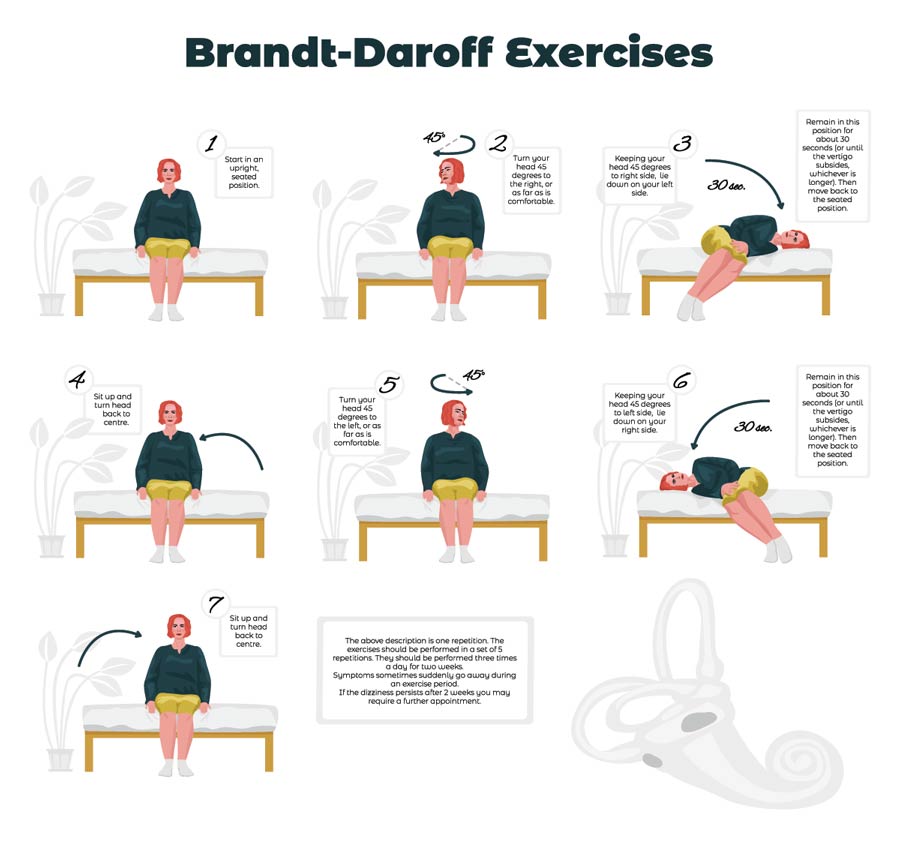

Treatment can then be tailored to the subtype of concussion. The previous cornerstone of concussion management was complete physical and cognitive rest. But no prospective randomized clinical trials confirmed this treatment strategy, particularly after the acute stages of sustaining a concussion. Certainly, cognitive rest is thought to be helpful in the cognitive subtype of concussion, but prolonged cognitive rest has the potential to worsen mental health issues such as depression, sadness, and/or hopelessness. This could adversely affect those with an anxiety/mood type of concussion. Similarly, it has been found that those with ocular or vestibular types of concussions benefit from specific rehabilitation and repositioning maneuvers to promote optimal recovery.

This challenges the concept that complete physical rest is necessary for recovery, specifically in ocular and vestibular concussions.

Obviously, more study is needed, but the approach to diagnosing and treating concussions continues to evolve. Vigilance for these types of injuries and protections for those at risk remains paramount in avoiding long-term complications. But in those who have sustained a concussion, awareness of updated approaches to management can be meaningful.

If you have been injured, contact Diller Law’s Personal Injury Lawyers for a free legal consultation. Call us at 617-523-7771.