Currently, American homes have adopted over 90 million dogs into their families. Without a doubt, these canines provide enjoyment and companionship to their owners.

Notwithstanding the camaraderie and comfort dogs afford, dog bites are an event that can occur for various reasons. For example, when dogs feel nervous, threatened, are protective, or when they don’t feel well, they can react to others by biting.

When a bite occurs, one in five individuals bitten by a dog needs medical attention, particularly when the bite results in penetration of the skin.

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that approximately 4.7 million dog bites occur each year. The highest rates of injury occur in children. This article discusses the risk of infection after a dog bite, types of infections, and treatment.

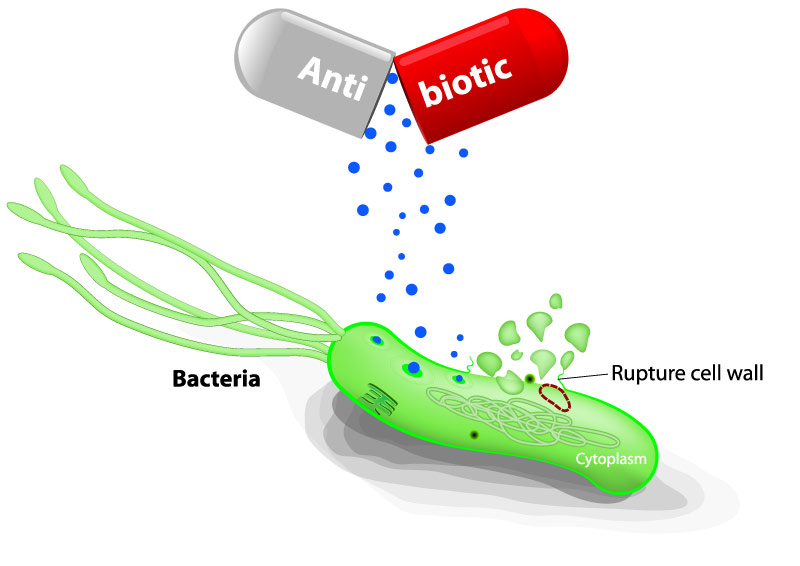

If a bite penetrates the skin, germs can be transferred from the dog’s mouth into the wound. A bite that involves the hands and/or feet is also known to be a risk factor for developing an infection. This is because the blood supply in these regions is less than regions closer to the heart. The average time from a bite to the appearance of symptoms is approximately 12 hours.

Many different types of bacteria are important to understand. Specifically, the type of bacteria involved in a bite can help dictate treatment.

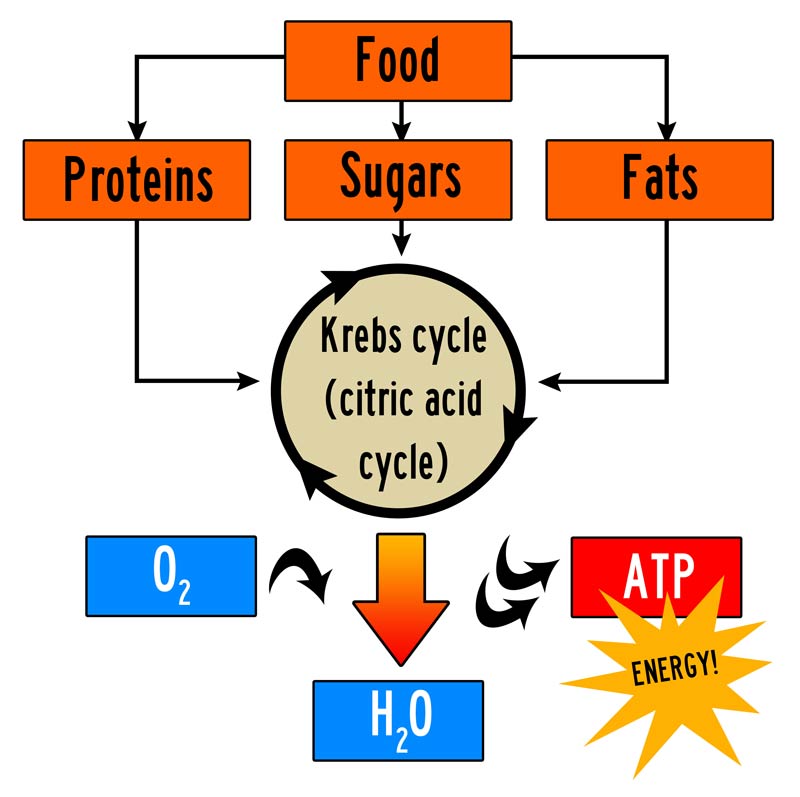

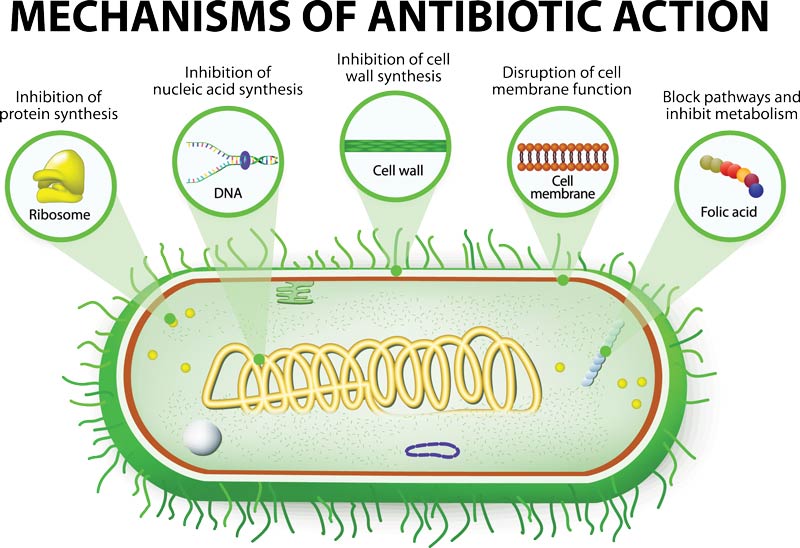

Broadly speaking, the type of bacteria that can invade a wound include aerobic bacteria and anaerobic bacteria. In simple terms, aerobic bacteria use oxygen to obtain energy and survive,

while anaerobic bacteria grow and obtain their energy without oxygen. The distinction is relevant because antibiotics may have more selectivity and effectiveness for one type of bacteria over another.

It is also noteworthy that some infections can occur that are mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections.

Among anaerobic bacterial species involved in bites, the most commonly isolated are Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Prevotella. These types of bacteria are also more common when a wound develops into an abscess, as opposed to cellulitis. An abscess refers to a collection of pus, or yellow liquid, where the bacteria and the body’s defense cells are attempting to eradicate the infection, but pool in one location in the body.

Cellulitis refers to an infection just below the skin’s surface and is characterized by swelling, redness, and a higher temperature in the region.

Finally, if an infection spreads to the bloodstream, a serious condition called sepsis is the result.

For aerobic bacterial species, there are many categories of bacteria that deserve particular attention. The most common bacteria with dog bites is from Pasteurella canis. (This is in contradistinction to cat bites where Pasteurella multocida is the most common organism.)

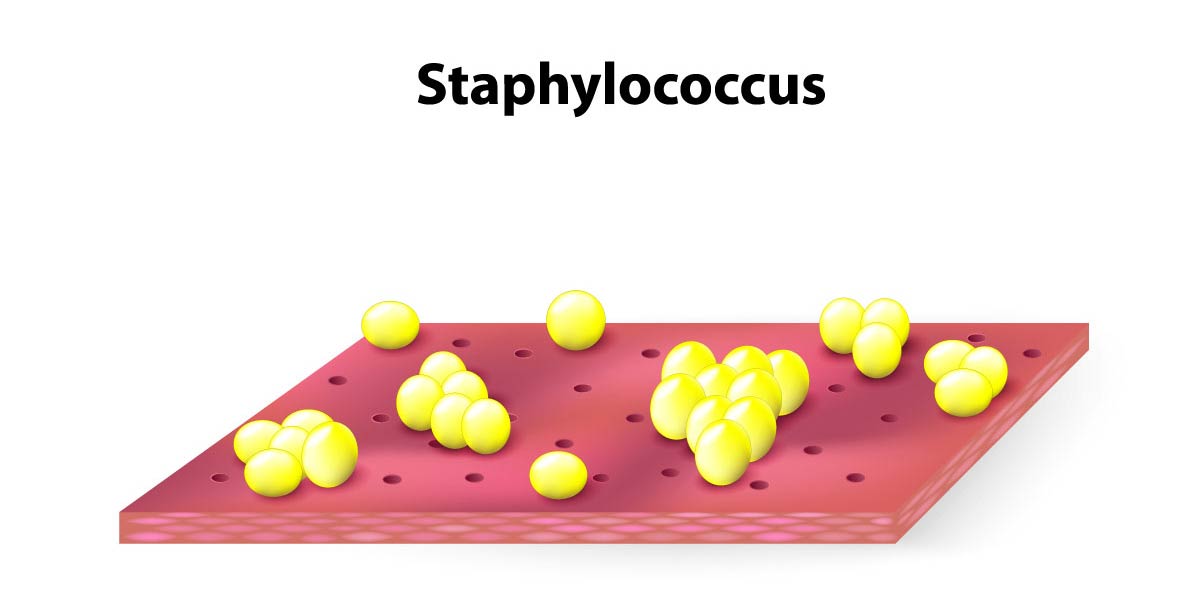

The next most common aerobic species include streptococci, staphylococci, and Moraxella.

Another type of bacterial infection to be aware of comes from the Capnocytophaga canimorsus organism. Although not as common as other bacteria, the fatality rate is relatively high (30%). The high fatality rate is related to the ability of Capnocytophaga to enter the bloodstream and cause sepsis. This type of infection can also be more severe in bite victims who have a compromised immune system. Individuals who have had their spleen removed or have impaired spleen function are also highly susceptible.

Interestingly, Eikenella corrodens is a bacterium more commonly seen with human bite infections, but is rarely be seen with dog bites.

Knowledge of the different types of the most common bacterial species is critical to initiating antibiotics before isolation of the species through culture. A culture involves swabbing the infected area and placing it in a dish that would allow the growth of bacteria.

If growth occurs, then identification can be performed. This process, however, has an inherent delay in obtaining culture results. In particular, time is needed for the growth of the bacteria, followed by the time needed to identify the bacteria. Cultures may take between 24 to 48 hours to return for aerobic bacteria. There are, however, some slower-growing organisms that can take five days or longer.

Treatment for dog bite infections can include home wound care, oral antibiotics, intravenous antibiotics, and surgical incision and drainage.

Home wound care for more superficial bites and/or as a temporizing measure until more definitive treatment is available, involves cleaning the bite wound with soap and water, placing a sterile bandage over the wound, and monitoring for signs of infection (redness, swelling, and increase in temperature). Information about the dog is also important to obtain such as the owner’s contact information and determining whether the dog is up to date on all vaccinations, including rabies.

Note it is unusual for dogs in the United States to have rabies, but if the dog’s status is not known, a series of shots will need to be administered to the bite victim. Because the signs and symptoms of rabies do not present until the infection is most severe, and often fatal, rabies injections are administered even if the bite victim does not have symptoms at the time of the bite.

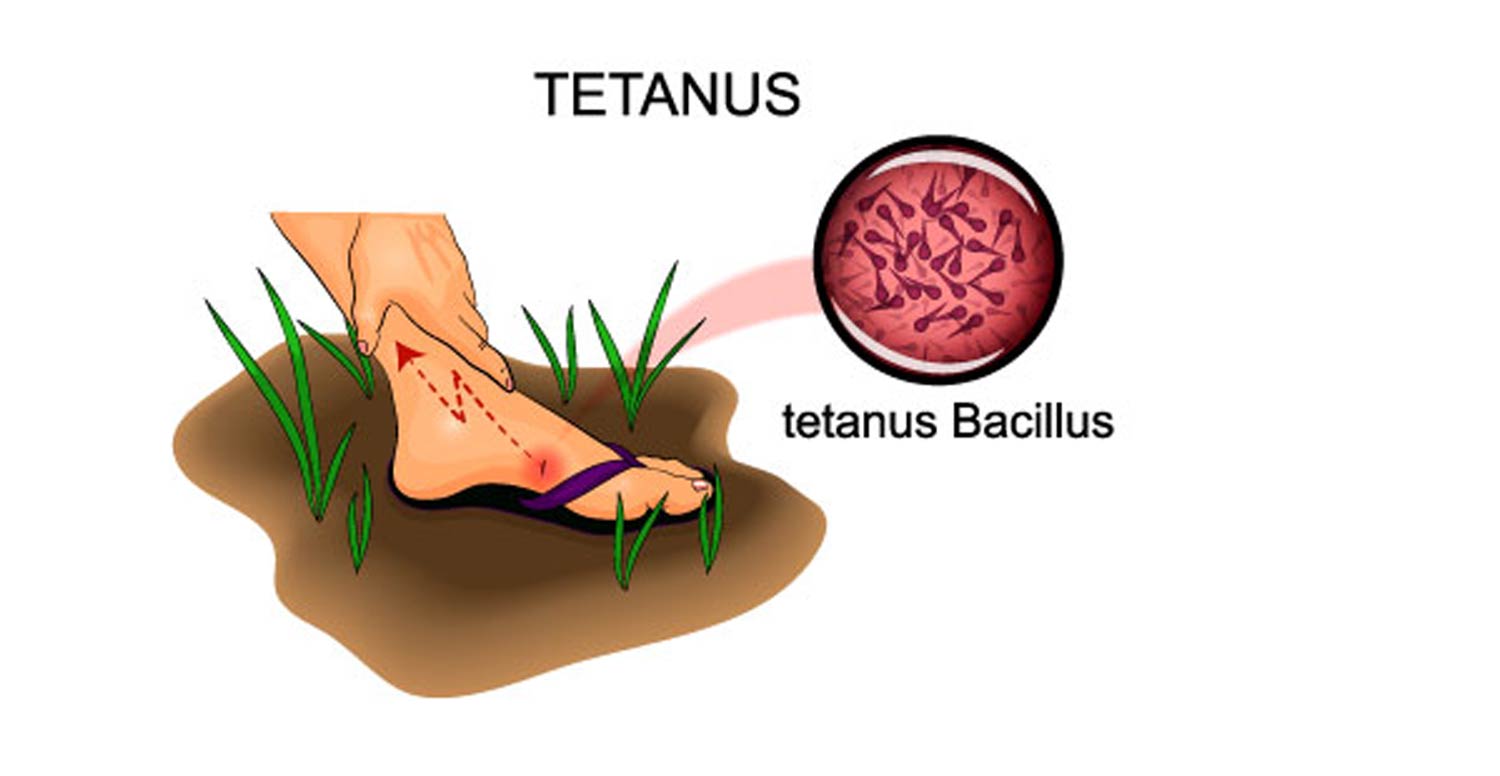

An evaluation of the bite victim’s tetanus status will also be performed. Although the risk of tetanus is relatively low, unless the wound has also been contaminated by soil, the tetanus toxoid should be administered following a high-risk bite and without a vaccination within 10 years. A booster dose is recommended if more than five years have elapsed since the last dose.

Oral antibiotics (taking the medicine by mouth) versus intravenous antibiotics (through the vein) depends on the severity of an infection. The most severe infections in which an abscess has formed will require surgical opening of the infection and removal of infected and devitalized tissue to promote healing. Antibiotics will likely continue after the surgery has been completed.

Dog bites represent serious injuries that can result in infection. An understanding of the types of infections and the various treatments may help avoid long term complications.

Dr. John, Esq. is both an attorney and a physician. Before obtaining his law degree, Dr. John Naranja practiced for approximately 12 years as an orthopedic surgeon.